With the introduction of the Atalanta, was Fairey Marine a ‘disruptor’?

Jim Sumberg and Nick Phillips

MARCH 2023

In today’s business world being recognised as a ‘disruptor’ is a badge of honour (and sometimes a ticket to riches). Disruptors see opportunities in mature markets, opportunities they seek to exploit by introducing new technology, new business models and/or new partnerships. Disruptors are not interested in incremental change, they are game-changers: if successful, they fundamentally reshape markets, or create whole new markets. Uber and Airbnb are classic examples of disrupters, but there are many others.

Of course, not all would-be disrupters are successful: moving from radical vision to market disruption, to say nothing of market domination, is neither straight-forward nor guaranteed.

Here we ask the question: with the introduction of the Atalanta, did Fairey Marine successfully disrupt the post-war market for small cruising yachts?

It is certainly arguable that in the run up to and immediately following WWII, the market for small cruising yachts in the UK resembled a mature market. While new yachts were being designed and built, there was little technical innovation. Boats were still built primarily from wood, in relatively small-scale yards, using long-established methods. With some notable exceptions, yachting was still very much a pursuit of adult men. The plywood and GRP revolutions were still over the horizon, as was the re-orientation toward family cruising.

Drawing from an earlier analysis1 we suggest four elements of Fairey’s foray into this market in 1956 had the potential to cause significant disruption.

Hot-moulding

First, was the use of hot-moulded wood veneers, a technology that had already proved its worth in other contexts, to construct a hull, deck and blister assembly that was both light and strong. While wood was still the primary construction material, hot moulding fundamentally changed the types and quantity of wood required, and the skills required to work it.

‘Production Line’ Build Process

Second, was the industrialisation of the building process, which was facilitated by hot-moulding. Fairey’s site on the Hamble River was more factory than boatyard; and its employees, more industrial workers than traditional craftsmen. The industrialised and standardised work routines that produced the Atalanta drew on Fairey’s experience of wartime airplane manufacture, and its post-war success with the mass production of sailing dinghies.

Engineering and Design

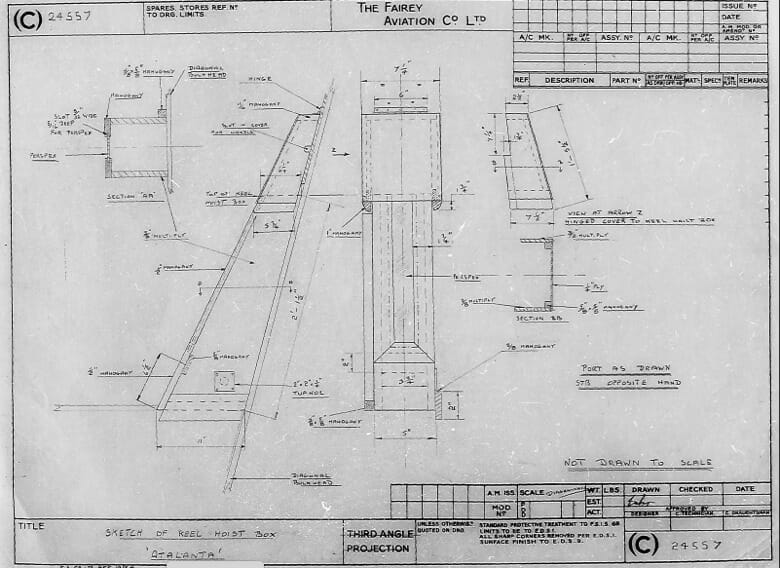

Third, was the way new design elements, such as the twin lifting keels, were engineered into the boats. For example, it is impossible to imagine the Atalanta’s keel lifting mechanism emerging from either the drawing table of a yacht designer or a traditional boatyard. It has ‘machine shop’ rather than ‘boat shop’ written all over it, directly reflecting Fairey’s expertise in aviation engineering. Any doubt about this can be quickly dispelled by inspecting the drawings for the Atalanta, which are available on the AOA website.

(sketch of keel hoist box)

Marketing

Fourth and finally, was the way that Fairey re-imagined the market for small cruising yachts. The Atalanta was portrayed and marketed as a trailable, seaworthy, comfortable family cruiser, qualities that were directly linked to hot moulding and lifting keels. The market segment that was targeted consisted of people moving up from dinghies to accommodate their growing families. This vision is captured in part in an image used in the marketing materials, showing two children enjoying the comfort and independence of the rear cabin.

(A26, 1957, original brochure)

So, with so much potential to cause disruption, what actually happened?

Over a 10-year period Fairey produced a total of 187 Atalantas, but by the late 1960s the company was no longer producing sailing cruisers. Other than the Atalanta (and its close relatives, the Fulmar, Titania and Atalanta 31), hot moulding was never used again to mass produce small cruising yachts. It is hard to argue, therefore, that hot moulding did much to disrupt the market (although it did lay the basis for cold moulding, which while still in use, has never been particularly popular for small production yachts).

Traditional wood construction was certainly on the way out, only Fairey had backed the wrong horse: it was GRP rather than hot moulding that would revolutionise yacht construction. However, Fairey’s model of industrialised yacht manufacture was completely compatible with GRP and it rapidly came to dominate the industry in other’s hands. And as Fairey rightly foresaw, the real growth potential was in the new market for affordable family cruisers.

We conclude that Fairey did not directly or significantly disrupt the small cruiser market through the introduction of the Atalanta. Nevertheless, the GRP-based disruption that was soon to follow built directly on some key contributions made by Fairey. Ironically, the company itself was not to profit from this disruption and the undreamed-of growth in the small cruiser market that soon followed.

Discuss ……